By Stephanie Namahoe Launiu

10 April, 2025

In the heart of downtown Honolulu, ʻIolani Palace stands as a majestic reminder of Hawaiʻi’s royal past — the only official royal palace on U.S. soil. Often called the “Grand Dame of Architectural Splendor,” she’s more than just a building — she’s the soul of a kingdom once lost. Surrounding it, a number of other historic sites dot the Iolani Palace area, painting a vivid picture of the monarchy, its legacy, and the pivotal moments that shaped modern Hawaiʻi.

Wander the grounds at your own pace to uncover stories of pride, resilience, and royal heritage woven into every stone — here’s what to explore.

Front view of ‘Iolani Palace (Photo Credit: ‘Iolani Palace)

Location: 364 King St. at the corner of King and Richards St.

A National Historic Landmark, ʻIolani Palace is the only royal residence in the United States. Built in 1882, it was the heart of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i’s political and social life until the monarchy was overthrown in 1893.

King Kalākaua, inspired by a meeting with Thomas Edison, transformed ʻIolani Palace into a modern marvel — installing electric lights, indoor plumbing, and telephones even before the White House. But just a few years later, the tides of history shifted. A group of American businessmen overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy, setting the stage for a somber chapter. In 1895, following a failed attempt to restore the crown, Queen Liliʻuokalani was tried in her own throne room and confined to an upstairs room under house arrest. She spent her remaining years in quiet exile, steadfastly refusing to recognize Hawaiʻi’s annexation by the United States.

Restored and reopened in 1978, today ʻIolani Palace stands as a museum and symbol of Hawaiian sovereignty, where visitors can walk the same halls once graced by kings and queens.

Stroll the palace grounds on your own or explore the grandeur of ʻIolani Palace on a guided tour. Available Tuesday through Saturday from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., you’ll be taken through the first and second floors. Tickets are available at the Hale Koa (ʻIolani Barracks) box office or deepen your connection by becoming a member of the Friends of ʻIolani Palace — members enjoy free admission, discounts, and exclusive perks.

Get tickets to tour the inside of Iolani Palace and its grounds.

Keli’iponi Hale, the Coronation Pavilion (Photo Credit: ‘Iolani Palace)

Location: On the ‘Iolani Palace grounds, facing King Street in the southeast quadrant

This is where King Kalākaua, nicknamed the Merrie Monarch, was coronated in 1883. It was here that the king crowned himself — ushering in the Kalākaua Dynasty and marking the end of the Kamehameha line.

The first reigning monarch to circumnavigate the globe, he met with leaders in countries from Japan and Egypt to France and the U.S. His 1874 visit to Washington, D.C., led to President Ulysses S. Grant hosting the first-ever dinner for a foreign Head of the State at the White House.

At his coronation, Kalākaua placed the crown on his own head, honoring the traditional Hawaiian belief that no one touches the head of an aliʻi nui (high chief or king). Though he had already been ruling since 1874, this symbolic moment solidified his reign.

The Coronation Pavilion is still used today to host official ceremonies, parades, and performances by the 40 members of the Royal Hawaiian Band — a tradition started by King Kamehameha III.

Pro Tip: Every Friday from noon to 1 p.m. they host a free public concert.

Hale Koa – ‘Iolani Barracks was built to house the Royal Guard (Photo credit: ‘Iolani Palace)

Location: On the grounds of ‘Iolani Palace, along Richards Street

Built in 1871 from coral blocks, this fortress-like structure once housed the monarch’s Royal Guard. It featured a mess hall, kitchen, dispensary, sleeping quarters, and jail. After the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and the Royal Guard’s disbandment, ‘Iolani Barracks found new roles — from sheltering refugees during the 1899 Chinatown fire to serving as the headquarters for the National Guard of Hawai‘i.

Originally located on what are now the grounds of the Hawaii State Capitol, the barracks were moved, stone by stone, to the current location in 1965. Hale Koa includes the Palace Shop, a ticket office, and a video theatre.

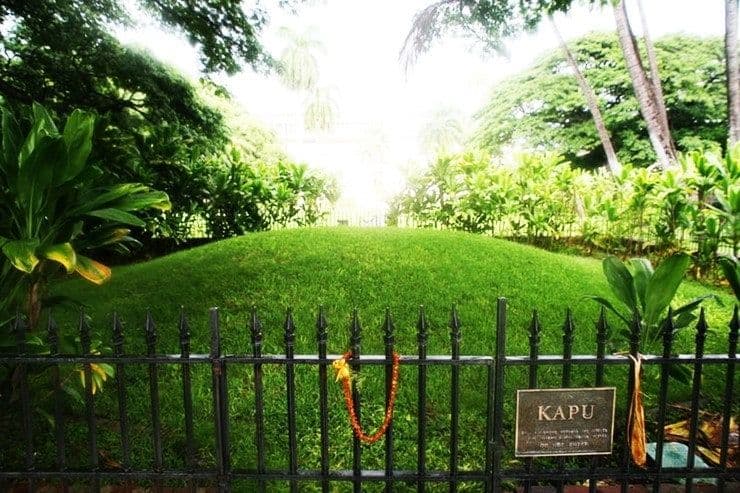

Fenced in grassy mound marks the spot where the remains of royalty once lay. (Photo credit: ‘Iolani Palace)

Location: Southeast quadrant of the ‘Iolani Palace grounds

Pohukaina or the Sacred Mound, is a fenced-in grassy mound that marks what was once the Royal Mausoleum. In 1825, workers built the structure of white-washed coral blocks to house the remains of Kamehameha II (Liholiho) and his Queen Kamāmalu. Both died of measles while on a trip to England.

Over the years, the ancestral remains of other aliʻi (high chiefs) were brought and buried at Pohukaina. It is said that high chiefs from as far back as the 1500s are buried here. In 1865, the remains of 21 ali‘i were removed from the location and carried in a torchlight procession to Mauna ‘Ala, the new Royal Mausoleum in Nu‘uanu Valley.

Over the years, the preservation and restoration of ʻIolani Palace have been a monumental effort. Beginning in the 1970s, the palace was meticulously restored to its original splendor, with many of its original furnishings and artifacts recovered, repaired, and replicated. The State of Hawaii and the Palace Preservation Society spearheaded the project with significant funding and resources.

In 1978, the palace was reopened to the public, transforming it into a cherished cultural and historical landmark. Today, ʻIolani Palace stands as a testament to the dedication and commitment to preserving Hawaii’s royal heritage, inviting visitors to step back in time and experience the grandeur of the Hawaiian monarchy.

Ali’iolani Hale was where the proclamation was publicly read overthrowing the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893. (Photo credit: State of Hawai’i)

Location: 417 S. King St. (across from ‘Iolani Palace)

You might recognize Aliʻiōlani Hale from the original Hawaii Five-0 — the iconic building made several on-screen appearances. Its real-life history is even more dramatic.

Meaning “House of the Heavenly King,” the building was originally intended to be a royal palace for Kamehameha V in 1872. However, the king ultimately designated it as a government center for the Kingdom of Hawai‘i. The royal residence would later be built nearby at ʻIolani Palace.

Aliʻiōlani Hale played a pivotal role in one of Hawai‘i’s darkest chapters. In the lead-up to the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, the Committee of Safety, led by Lorrin Thurston and backed by American sugar interests, met on the building’s second floor to plan the coup. On January 17, 1893, after U.S. troops landed and positioned cannons toward the palace, a proclamation from Aliʻiōlani’s balcony declared Queen Liliʻuokalani deposed. To prevent bloodshed, the Queen surrendered peacefully to what she called “the superior force of the United States of America.”

Today, Aliʻiōlani Hale houses the Hawaiʻi State Supreme Court and the Judiciary History Center, featuring exhibits, a restored courtroom, and a deeper look into the islands’ legal and political past.

The King Kamehameha statue is decorated with flower leis on his birthday, June 11. (Photo credit: State of Hawai’i)

Location: In front of Ali‘iolani Hale

The iconic Kamehameha I statue may be one of the most photographed spots in Honolulu — but it’s not the original.

Commissioned by King Kalākaua to mark the 100th anniversary of Captain Cook’s arrival, the statue was sculpted in Italy and cast in France. En route to Hawai‘i, it was lost in a shipwreck off South America. A second casting was quickly made and unveiled during Kalākaua’s 1883 coronation, where it stands today.

Fun Fact: The original statue was later salvaged and sent to Kapaʻau in Kohala on the Big Island —Kamehameha’s birthplace. Since then, two more replicas have been made: one for the U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C., and another initially created for Kaua‘i, which was later installed in Hilo, where Kamehameha once ruled.

These were the first permanent houses built for the American missionaries who came to O’ahu in 1821. (Photo credit: State of Hawai’i)

Location: 553 S. King St.

American missionaries arrived in Kona on the Big Island in 1820, the year after Kamehameha I died. The following year, a new group of missionaries traveled to O‘ahu to spread the gospel further. Area chiefs welcomed them, and Kamehameha II granted them land to settle on. Hawaiian laborers built temporary thatched homes, followed by more permanent Western-style structures.

The Hawaiian Mission Houses (HMH) are some of the oldest surviving structures on O‘ahu and a National Historic Landmark. Visitors can explore how the early Protestant missionaries lived in buildings that have survived for over 200 years.

HMH preserves Hawai‘i’s oldest Western-style house, built in 1821, along with the 1831 Chamberlain House, the 1841 Bedroom Annex, a historic cemetery, a collections vault, a gift shop, and multipurpose spaces. The site also includes a research library and archive with over 80,000 digital items, including one of the world’s largest collections of Hawaiian-language printed materials. Through school programs, guided tours, and award-winning historical theater, HMH brings history to life.

Kawaiaha’o Church still holds weekly church services and is an active community resource. (Photo credit: Kawaiaha’o Church)

Location: 957 Punchbowl St.

Built on sacred land once granted to the missionaries, Kawaiahaʻo Church stands as one of Hawai‘i’s most revered historic sites. The land was home to a freshwater spring cherished by Chiefess Ha‘o, giving the church its name — Ka Wai a Ha‘o, or “the water of Ha‘o.”

Nicknamed “The Great Stone Church,” it was constructed from 14,000 hand-chiseled coral blocks and quarried underwater by Native Hawaiians who dove up to 20 feet deep. It took five years of labor, with the church dedicated in 1842 before a crowd of 5,000, including King Kamehameha III.

Known as both the “Westminster Abbey of the Pacific” and “The Church of the Ali‘i,” Kawaiahaʻo is a state and national historic landmark. Just east of ʻIolani Palace, it remains an active place of worship, with Sunday services at 9 a.m., and is considered the premier Hawaiian Congregational Church on the islands.

Download a free audio tour of Kawaiaha’o Church and its history.

Kawaiaha’o Fountain beside the church. (Photo credit: Kawaiaha’o Church)

Location: On the left side of the church building as viewed from the front entrance

Tucked beside the church, a natural freshwater spring still flows gently from a stone outcrop. This spring, cherished by Chiefess Ha‘o, has long been regarded as a source of sustenance and serenity. Though simple in appearance, its quiet presence connects visitors to the deep cultural and spiritual roots of the land.

The Tomb of Lunalilo who wanted to be buried closer to the people. (Photo credit: Kawaiaha’o Church)

Location: On the right side of the path leading up to the Kawaiaha‘o Church entrance

King Lunalilo, the sixth monarch of Hawai‘i, ruled for just one year but left a lasting legacy. The People’s King was deeply loved by commoners, championed democracy, and believed leadership should be chosen by the people — not inherited by bloodline.

Though his predecessor, Kamehameha V, didn’t name a successor, the legislature appointed Lunalilo. He insisted on a public vote and became Hawai‘i’s first elected monarch in 1873. Before his untimely death at age 39 in 1874, Lunalilo requested to be buried at Kawaiaha‘o Church, among the people he served, rather than at the Royal Mausoleum with other ali‘i.

Washington Place, the personal home of Lili’uokalani. (Photo credit: State of Hawai’i)

Location: 320 S. Beretania St.

A designated National Historic Landmark, the former personal residence of Queen Liliʻuokalani and her husband John Dominis, played a central role in Hawai‘i’s history — from the final days of the monarchy to its path to statehood in 1959. It also served as the official residence for Hawai‘i’s governors from 1919 to 2002.

While Washington Place continues to host official events and ceremonies today, the governor resides in a newer home behind it on the same grounds. It is open to the public for free tours every Thursday at 10 a.m. Spots book up quickly — reserve yours here.

A virtual tour is also available at https://washingtonplace.hawaii.gov/tours-and-gardens/.

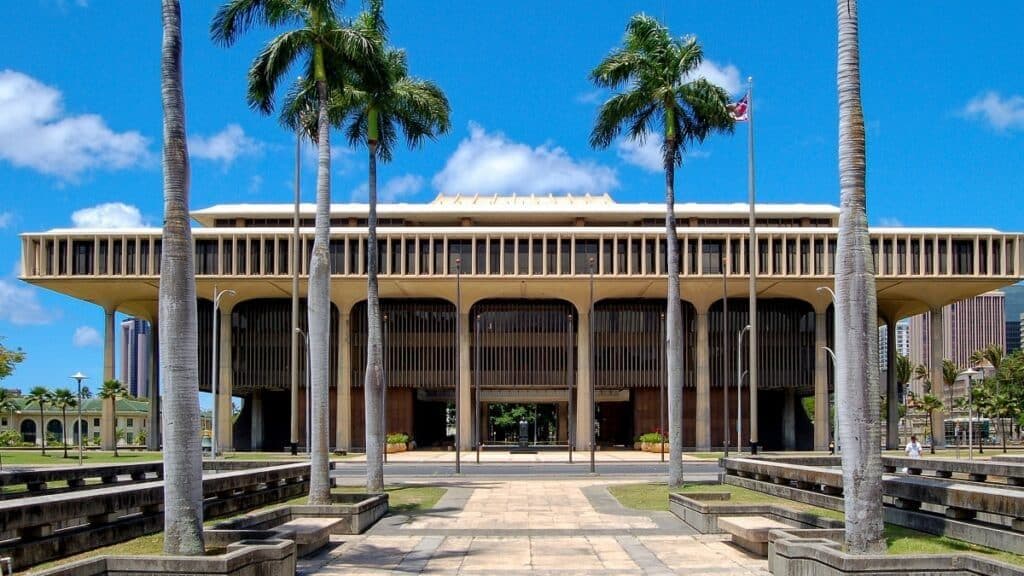

The Hawaii State Capitol is the official capitol building of the U.S. State of Hawaii (Photo credit: State of Hawai’i)

Location: 415 S. Beretania St.

The Hawai‘i State Capitol houses the offices of the Governor and Lieutenant Governor, state legislators, and the chambers of both the House and Senate. Hawai‘i Governor John Burns commissioned the building in 1965 and completed it in 1969. Designed in the style of “Hawaiian international architecture,” the Hawai‘i State Capitol embraces the natural elements of the islands. Its open-air layout is surrounded by a reflecting pool that symbolizes the Pacific Ocean. At its center, an atrium opens to the sky, inviting sunlight, wind, and even rain to flow freely through the space — a living connection to Hawai‘i’s environment.

Learn more about the significance behind the architectural details of the Hawaii State Capitol.

Liliuokalani Statue stands between ‘Iolani Palace and the Capitol Building. (Photo credit: State of Hawai’i)

Location: Between the State Capitol and ‘Iolani Palace

“The Spirit of Liliʻuokalani” is a six-foot bronze statue honoring Hawai‘i’s last reigning monarch. Created by artist Marianna Pineda, it was cast in Boston and dedicated on April 10, 1982. The sculpture portrays Queen Liliʻuokalani as a dignified sovereign, cultural guardian, and composer. In her left hand, she holds three powerful symbols of her legacy:

The sheet music for “Aloha ‘Oe,” her most beloved composition

A page from the 1893 Hawai‘i Constitution

The Kumulipo, the ancient Hawaiian creation chant she translated during her 1895 imprisonment

Her placement isn’t just symbolic. As scholar Manalo-Camp noted, the Queen isn’t merely “keeping an eye on the legislature,” she walks among the people, ever present in the civic and cultural heart of Hawai‘i.

Use these addresses to customize your own historic walking tour around the ‘Iolani Palace district.

Happy Exploring!

Join our newsletter for travel inspiration, insider tips and the latest island stories.

By subscribing, you agree to receive emails from Hawaii.com. You can unsubscribe anytime. See our Privacy Policy.