By Stephanie Namahoe Launiu

Just seven miles off the southern coasts of Maui and Lāna‘i, Kahoolawe Island is a rust-colored silhouette on the horizon. At less than 45 square miles, it’s the smallest of Hawai‘i’s main islands — but don’t mistake size for insignificance. Unlike the bustling shores of Oʻahu or the lush valleys of Kaua‘i, Kahoʻolawe’s story runs deep.

There are no hotels, no restaurants, and no residents here. Just wind, waves, and a profound stillness. As the only island without permanent human habitation, it’s a story etched in ancient navigation routes, wartime scars, and cultural revival.

Kahoolawe (Shutterstock)

Kahoʻolawe’s dry terrain and lack of fresh water made large-scale settlement nearly impossible. Even in ancient times, its population was sparse, limited to small coastal fishing villages that sustained life by the sea. But despite its remoteness, the island’s fate would become riddled with conflict.

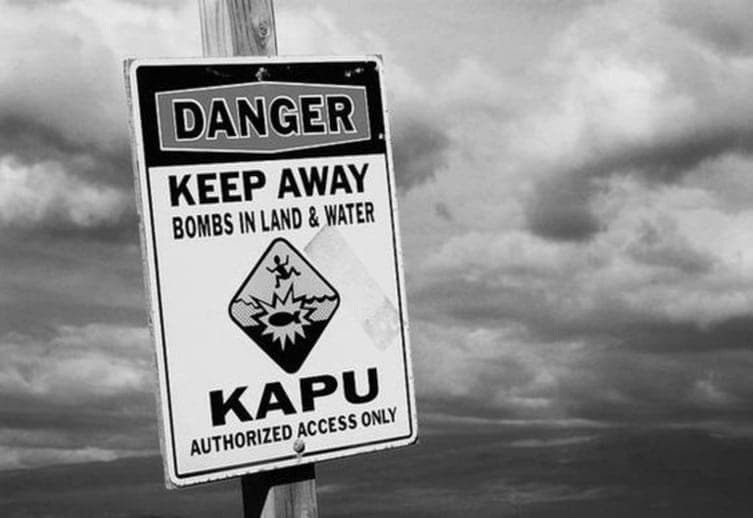

In the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. military placed Kahoʻolawe under martial law, transforming it into a live-fire training ground. Bombs fell from the sky and missiles struck her cliffs. The island — sacred to many — was now a target, earning the nickname “Target Isle.”

Can you imagine standing on the beach, watching plumes of smoke rise from the horizon as bombs rained down on an island in the distance? For decades, that was the reality.

But resistance grew. Native Hawaiians, led by the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO), protested, filed lawsuits, and staged occupations. Their movement wasn’t just about stopping the bombing — it was about protecting the sacred land.

In 1990, after years of advocacy, the island’s stewardship began to shift. President George H.W. Bush ordered a halt to the bombing, and by 2003, control of Kahoʻolawe was formally returned to the State of Hawaiʻi.

Today, the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) manages the island and the surrounding waters, focusing on cultural restoration, environmental healing, and education. Efforts have focused on removing UXO, controlling erosion, and reintroducing native vegetation. The long-term vision is to return Kahoʻolawe to a Native Hawaiian entity — fully and forever.

Archaeological evidence indicates that Polynesians settled on Kahoʻolawe around 1000 A.D., establishing small fishing communities along the coastline. The island’s strategic location made it a vital center for navigation and voyaging.

Notably, Puʻu Moiwi, a remnant cinder cone, served as the site of the second-largest basalt quarry in Hawaiʻi, providing material for stone tools such as adzes. The inhabitants constructed stone platforms for religious ceremonies. They erected shrines to ensure successful fishing expeditions and carved petroglyphs into the rocks, many of which remain today. Traditionally, Kahoʻolawe is dedicated to the sea god Kanaloa.

The island’s arid environment and limited freshwater sources likely restricted its population to a few hundred individuals. The largest settlement, Hakioawa, at the northeastern end facing Maui, may have housed up to 120 residents at one point.

A kapu sign warning of unexploded ordnance (Photo Credit: Hawaiianscribe)

Today Kaho’olawe is for Native Hawaiian cultural and spiritual practices. Native Hawaiian groups are caring for the island. They have a vision of restoring Kaho’olawe to a healed island surrounded by pristine ocean waters and healthy reef ecosystems. Native Hawaiians consider Kaho’olawe to be a living spiritual entity.

Hawaiians have a special relationship with their lands. They call it “aloha ‘āina,” a concept that embraces the animals, plants, and climate. Aloha ‘āina means caring for and maintaining a unique and special connection to the land of one’s ancestors, birthplace, the land and the ocean that feeds, and where one lives and works. Aloha ‘āina is a deeply felt appreciation that comes from knowing a place’s history, traditions, and one’s connection to it.

Kaho‘olawe is recognized by federal, state, and county governments as a wahi pana (special place) and a pu‘uhonua (place of refuge). As a wahi pana, the island is dedicated to Kanaloa, the honored and respected ancestor/deity who cares for the foundation of the Earth and the atmospheric conditions of the ocean and the heavens. As a pu‘uhonua, Kaho‘olawe is a refuge, or “safe” place for people to practice and live aloha ‘āina that, in turn, guides the care and management of the island and its surrounding waters.

A Native Hawaiian practitioner prepares for a cultural ceremony on Kaho’olawe. (Photo credit: Kahoolawe Island Reserve Commission – KIRC)

Kaho‘olawe Island has faced significant environmental challenges due to its history as a bomb range and training ground in World War II. The relentless military exercises left the island scarred, with unexploded ordnance scattered across its landscape, posing a continuous threat to restoration efforts. The introduction of non-native species, such as feral cats, goats, and sheep, further exacerbated the island’s ecological woes. These invasive species wreaked havoc on the native vegetation and wildlife. Feral cats, in particular, have been a major threat to the island’s seabird populations, including the endangered Hawaiian petrel and the Newell’s shearwater.

The Kaho’olawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) has been tirelessly working to mitigate these impacts. However, the process is painstakingly slow due to the island’s remote location and the persistent danger of unexploded ordnance. Despite these challenges, the KIRC remains committed to restoring Kaho‘olawe’s natural habitats and ensuring the survival of its unique ecosystem.

The Kahoolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) has been at the forefront of efforts to restore and conserve the island’s natural and cultural resources. Their work involves a multifaceted approach, focusing on the removal of invasive species, the replanting of native vegetation, and the protection of cultural sites and artifacts. The commission’s dedication to preserving Kaho‘olawe’s cultural heritage is evident in their meticulous efforts to safeguard the island’s historical and spiritual significance.

In collaboration with organizations like Island Conservation, the KIRC has developed innovative solutions to address the island’s environmental challenges. One such initiative is the deployment of a new camera system, called Sentinel, to help remove invasive feral cats from the island. These efforts are crucial in restoring the island’s ecological balance and ensuring the survival of its native species. The KIRC’s comprehensive management plan aims to protect Kaho‘olawe’s natural resources and cultural heritage for future generations.

Healing Kahoʻolawe is a monumental task — and one that has relied heavily on the hands and hearts of volunteers. Over the years, thousands of people have contributed to reforesting the island, stabilizing erosion, restoring cultural sites, and monitoring fragile marine ecosystems.

Volunteer groups have helped:

Plant native vegetation to hold the soil in place

Build infrastructure to support future restoration

Conduct species and fish surveys in surrounding waters

Support cultural protocols and preserve sacred sites

But restoration doesn’t come easy — or cheap. With significant cuts in both federal and state funding, the future of Kahoʻolawe’s recovery remains uncertain. What was once a thriving volunteer program — hosting weeklong trips nearly every week — has now been reduced. At its peak, the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) maintained a two-year waitlist of eager volunteers. Today, those trips have been scaled back to once a month, and even those depend on resources that aren’t guaranteed.

Currently, the KIRC prioritizes volunteers who are affiliated with organized groups dedicated to restoring the island. It’s not just about labor — it’s about kuleana, the responsibility and privilege to care for this land.

If you’re interested in learning more, get in touch with the Kahoʻolawe Island Reserve Commission at 811 Kolu St., Suite 201, Wailuku, HI 96793. Call 808-243-5020 or email kirc.administrator@hawaii.gov.

Explore the KIRC website

Subscribe to their mailing list

Check out their Volunteer Program

Review the living library and online collection of Kahoolawe photos and memorabilia at the Bailey House Museum in Maui. It’s amazing!

Check out their in-kind donation wish list and give what you can.

Join our newsletter for travel inspiration, insider tips and the latest island stories.

By subscribing, you agree to receive emails from Hawaii.com. You can unsubscribe anytime. See our Privacy Policy.